Dallas Hates Trees

The Giving Trees: The Great Trinity Forest works like a lung for Dallas. But the city has no management plan for it. Photo by Scot Miller.

Published May 2015 ,By ZAC CRAIN / D MAGAZINE

The city has always made it easy to knock down trees in North Dallas. Now that the only land left lies to the south, the rules could change. What’s at stake? Just an urban canopy worth $9 billion.

Dwaine Caraway may exaggerate from time to time, but he doesn’t sugarcoat much.

So when the city councilman leads a tour of his district—a rambling, woody area just south of downtown that he has represented since 2007 and lived in since the 1960s—he doesn’t show off just his success stories. He makes sure to point out the problems his constituents face, too: stray dogs, obvious drug houses, orphaned plastic bags, grown men with sagging pants. And—

“See those trees?” Caraway asks, after pulling his black BMW 750i to the side of the road, halfway across Cedar Crest Bridge. The bridge is nestled in the Great Trinity Forest like a ribbon in an unruly head of hair.

“I want to cut all those trees back,” Caraway says, dismissively waving them away with the back of his hand, a king refusing his subjects. The scenic view is blocking what he really wants people to see: the downtown Dallas skyline and all the possibilities it holds.

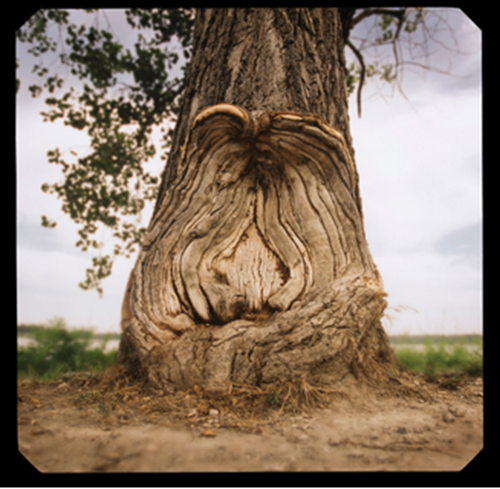

A Cottonwood tree. Photo by Dave Shafer.

Caraway keeps circling back to the topic as we continue on our tour of his district, picking up where he left off when he sees another stand of trees that are in his way—behind the tumbledown houses near the Columbia Packing Co., for example, or down the hill from the Walmart he brought in to anchor the Glen Oaks Crossing development off Ledbetter Drive. “Now, of course, all these need to go,” he says of the latter bur oaks, barely pausing, because it is obvious. Caraway already fought to get rid of the trees that gave Glen Oaks its name. No one should expect him to make an exception for this thicket.

For Caraway, the trees create a psychological barrier as much as a physical one. They are in the way of an idea. And if you look at it from that perspective, his animus toward the trees makes sense. He wants to see. He wants the people in his district to see how close they are to downtown, because it will make them feel part of something bigger. He needs developers to see how close the area is to downtown so they will realize its potential worth.

And that is why trees in Dallas are poised to become a racial issue. Caraway will be term-limited out of office this month, but his ideas about development will be carried forward by his successor. Much of the city’s developable land lies within District 4 and its neighbors in the southern sector. But that is also where development could do the most damage to Dallas’ tree canopy. Nearly 40 percent of it lies south of I-30, and a significant chunk of that percentage is on land where trees are largely unprotected. As much as 20 percent of the city’s total canopy could vanish, all because Dallas has never given a damn about trees.

The only barrier between the trees and a bulldozer is Article X of the city development code. But the ordinance—on the books since 1994 and misleadingly titled “Landscape and Tree Preservation Regulations”—has never offered much resistance, which is why it has been up for revision almost from the beginning. The City Council is expected to finally vote on an amended version later this year, and an update might make it harder for southern Dallas development.

But that won’t solve the city’s tree problem, because it’s not just the trees in District 4 that are in danger. They all are. In addition to a weak, development-friendly tree preservation ordinance that doesn’t actually preserve trees, there is no management plan in place for the Great Trinity Forest, and no staff in place to implement a plan if we did have one. The city has no forestry division—Dallas is one of the largest U.S. cities without one—and only hired its first forester less than a decade ago. The tree canopy is under attack in every corner of Dallas, as decades of shortsighted policy decisions begin to take their toll.

The good news is that we finally know exactly what’s at stake: an asset worth $9 billion.

Trunk Show: Matt Grubisich, the Texas Trees Foundation's director of operations, headed up the first comprehensive study of Dallas' tree canopy. Photo by Billy Surface.

On the morning of February 5, a curious mix of men and women gathered at Arlington Hall at Oak Lawn’s Lee Park to eat mini quiches and learn about trees. The Texas Trees Foundation—a nonprofit born in 1982 as a sort of booster club for the Dallas parks system—was formally presenting its State of the Dallas Urban Forest Report. Since it was the first-ever comprehensive survey of the city’s trees and the benefits they provide, this morning had been a long time coming.

Mayor Mike Rawlings sat stage right, at a front table with Lyda Hill, the billionaire philanthropist who helped fund the study. Developer Jack Matthews was at another round table up front. The guest of honor, Matt Grubisich, TTF’s director of operations, was stage left, sitting with Willis Winters, the owlish director of the Dallas Park and Recreation Department.

The back of the room was largely filled with folks in baggy earth-tone sport coats that they wore like a punishment. Each table seemed to have at least one guy with a Grizzly Adams beard or a ponytail or both. Others wore logo-branded polo shirts tucked into khakis with holstered phones. You would have no trouble locating a pocketknife.

Before the findings of the report were discussed, Mayor Rawlings talked about how he loved “the poetry and science and almost theology of trees” and stated the obvious: “When you mention Dallas, you wouldn’t necessarily think of trees.” That’s why, he said, trees are so important here.

A few more speakers took their turns in front of the crowd, and then Grubisich was finally brought to the stage. He looked more at home in his coat and tie than most of the other foresters and arborists in the room, but a close observer could see that he is one of them, someone used to getting his hands dirty on a regular basis. On his ring finger, there is a tattoo where a wedding band should be, a permanent replacement after losing the real thing too many times.

Grubisich explained that he and his team—six college interns and Tyler Wright, another urban forester with Texas Trees—collected data for the report over 11 weeks in the summer. They looked at 621 randomly selected plots around the city, each about one-tenth of an acre. Each tree within a selected plot needed to have measurements taken of about 20 attributes, including total height, trunk diameter, the size of its leaf area, and what percentage of that was missing.

After they had finished their work, the data was analyzed using i-Tree’s Eco program, open-source software developed by the USDA Forest Service to “quantify urban forest structure, environmental effects, and values to communities.” The results of the Eco assessment were combined with two other studies the foundation had worked on—a roadmap to tree planting and planning, in 2010, and a survey of open space completed in 2013. They looked at the Forward Dallas plan and the Grow South initiative, transportation corridors, TIF boundaries, heat island maps, anything and everything that could possibly impact Dallas’ tree canopy. What they found:

• There are 14.7 million trees spread over Dallas’ 340 square miles of land, with 37 percent of the tree canopy located south of I-30.

• Annually, those trees provide $9 million in energy savings, capture almost 60 million cubic feet of stormwater runoff (saving $4 million in repairs), and store 2 million tons of carbon valued at $137 million.

• There are 1.8 million potential tree-planting sites in the city.

• The Great Trinity Forest is responsible for almost 20 percent of the benefits derived from trees, though it covers only a sixth of the land.

• The big one: the structural value of Dallas’ trees—based on the size, species, and condition—is $9.02 billion. “Who says money doesn’t grow on trees?” Grubisich said. It may be a corny, practiced line, but it is hard to resist.

After Grubisich finished his PowerPoint presentation, the rest of the morning’s program focused on the future, and that almost entirely centered on tree planting. The goal is to add 3 million trees to the urban forest by 2022. The foundation has already secured various partners to help with its Tree North Texas plan, targeting the Medical District, Dallas ISD schools, and downtown.

It’s a noble goal and a crucial part of any tree management strategy. But left unsaid by everyone who took the stage that morning is this: what is the city doing to hang on to the trees it already has? Dallas is not proactively caring for its trees, so it will always be playing a losing game, no matter how many trees it plants.

“You’re not preventing things from becoming problematic,” says Micah Pace, an urban forestry specialist and certified arborist with the tree care company Preservation Tree Services. He was previously the Texas Forest Service’s regional urban forester for North Texas, from 2009 to 2013. Pace was seated at a table behind me at Arlington Hall. “It’s really a question of budget and investment. Any city’s going to tell you, well, we have limited resources. Well, of course you do. But it’s one thing to say you don’t have the money to do it, and another to say we choose to do other things with our investments and resources. The city has never historically invested in the urban forest the way that they should. And it’s evident.”

The urban forest report, Pace points out, wasn’t initiated by the city. “That tells you a lot right there.

Heart of Oak: The city might not have many employees looking out for trees. But at least it has Karen Woodward. Photo by Billy Surface.

Less than 100 years ago, a report on the urban forest could have been done in an afternoon. Most of the trees Grubisich and his team looked at weren’t here then and shouldn’t be here at all.

Dallas’ origin story—short version: it had no real reason to exist and was only brought to life through the steely-eyed determination of its business and civic leaders—has long been considered self-aggrandizing hogwash. But it’s not entirely untrue. It does help explain how a city built on a flat and treeless expanse at the bottom of the Great Plains now has 14.7 million trees.

There are more trees in Dallas than in Toronto, which has a similar land mass. There are more trees here than in New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., combined. Even out of context, that is a large number and certainly an unexpected one, given that the city is normally associated—if not synonymous—with concrete and steel and various other impervious surfaces.

Before Europeans arrived in North America and for centuries after, much of the land within the current city limits—especially north of the Trinity River—was blackland prairie. Wildfires and hungry herds of bison ensured it remained that way, promoting the growth of soft-stemmed herbaceous plants over anything with woody tissue. Trees did grow around the Trinity, mostly to the south, where spring floods and the deep alluvial soil deposited by the river nourished a hardwood forest of elm, hackberry, oak, and ash. But the fertile ground that kept that hardwood forest well fed also made it ideal for cotton and sorghum and just about anything else that could be cultivated. After John Neely Bryan came here from Arkansas in the 1840s, much of the forest was clear-cut and divided into farms.

Given all that, how did the city get a tree canopy four times the size of the one in Calgary? It happened relatively recently. You could say Dallas’ trees are part of the baby-boom generation.

Trees grew south of downtown after the farms were abandoned in the 1940s. Nature reclaimed the land through benign neglect, as seeds were washed into the river, floated south, and formed what we know as the Great Trinity Forest—less a sequel than a reboot of the original. It is now touted as the largest urban hardwood forest in the country, just one modifying word short of being suspect. It is a product of the way nature has always produced forests. Trees drop seeds, the seeds become other trees that grow, live, die, and finally break down and provide nutrients for their replacements.

But there is nothing natural about the tree growth north of downtown. It began around the same time as the river-bottom forest began to return, as new highways and the postwar population boom expanded the city’s reach. Blackland prairie is fine for grazing bison but less desired by homebuyers, so trees were planted. While commercial development is often an adversary of trees, residential development—in Dallas, anyway—is practically Johnny Appleseed. Grubisich of the Texas Trees Foundation says that roughly 90 percent of the trees in the northern half of the city were planted.

“You can track what was popular during a particular time in the nursery trade if you know when a house was built,” he says. Most of those trees were planted postwar, which means some of them are nearing the end of their life spans.

Yet it’s still a young forest. And maybe that’s the answer. Maybe Dallas has never made protecting trees a priority because it is still getting used to having trees to protect.

Article X was added to the city development code in 1994 for that purpose. It is an expanded version of the city’s original landscape zoning ordinance, which was enacted in 1986. Four years later, the City Council resolved “to support the protection and preservation of trees across the city.” That, after the usual round of negotiations and committee meetings, led to Article X. But the ordinance—from the very beginning—has had fewer teeth than a toddler, and it doesn’t have much to do with preservation, even though that word is in its title. Despite what they are called, the Landscape and Tree Preservation Regulations mostly deal with mitigation, with what a developer has to do when he decides it’s not worth the time or money to save a tree.

For almost the entire existence of Article X, people have tried to change it. Yet nothing of any substance has ever been done, other than an amendment in 2003 to protect fewer trees. (Eastern red cedars and mesquites are now only subject to mitigation if their trunks are 12 inches in diameter or greater; before it was 8 inches.) Former Mayor Laura Miller established the Dallas Urban Forest Advisory Committee in 2005 when she was still in office, but the group’s recommendations have yet to reach the full City Council.

Steve Houser, the committee’s chairman emeritus, recently gave me a 20-minute disquisition on the recent, very complicated history of Article X. Houser was expanding on an op-ed piece he wrote for the Dallas Morning News in late January, where he fumed, “Trees are lower on the Dallas list of priorities than plastic bags.”

“That really kind of steamed a few people,” he says, laughing. “But that’s okay. When a plastic bag ordinance flies through, and yet [an ordinance concerning] the trees that clean our air, our water, and our soil sits for four years, something is wrong.”

Article X is with the City Plan Commission’s Zoning and Ordinance Committee, and from there—after input from environmental groups, developers, average citizens—whatever is left will be taken to the full commission, and then the City Council. No one I talked to has much hope that what finally emerges will be much stronger. That means more situations like the one still unfolding near Uptown.

On February 1, the old Xerox building off Central Expressway just north of Haskell Avenue was imploded to make way for a controversial Sam’s Club. You would be forgiven if you thought any nearby trees would have been obliterated in the process. Considering that, it seems like a miracle—given recent history—that a grove of 100-year-old live oaks on the site is still standing.

But just because they remain there doesn’t mean they are safe. According to Article X, if Sam’s Club ultimately decides to remove them, all it will be required to do is pay into the reforestation fund (a few thousand per tree, chump change for a multimillion-dollar deal) or plant enough 2-inch saplings somewhere in the city to equal the total size of the trees removed. Doing that is like putting a quarter into the bank and waiting for the interest to turn it into a dollar.

Either way, it would take decades to recover from the loss of just one of the mature oaks on the Sam’s Club site, much less several of them. In aesthetic terms, of course, but also in the loss of potential carbon storage, oxygen production, pollution removal, and avoided runoff—a large bur oak, for example, can intercept 2,000 gallons of water in a year. Live oaks only make up 2 percent of the tree canopy but account for 10 percent of all tree benefits. Trees raise property values and reduce heat, and studies have tied them to lower crime rates. A big-box store with a massive parking lot could use all of that. It may lower construction costs to remove the trees now, but it could end up costing just as much in other ways.

At the Sam’s Club site, the cost will be comparatively minimal. But south of I-30, it could be astronomical. The Glen Oaks Crossing development already took down a huge swath of oaks to make way for a Walmart and QuikTrip and a dozen other stores. That’s not a cautionary tale in the southern sector. That is the ideal model.

“You’re not going to grow south until you knock some of those trees down,” Mayor Pro Tem Tennell Atkins told the City Council’s Quality of Life Committee last February.

You can’t blame Atkins or Caraway or anyone else for bristling at the notion that now Dallas should make it more difficult to remove trees, since most of the northern half of the city is already built out. Sure, yeah, change the rules after the other team has already won the game. They’d get rid of the entire preservation ordinance if they could, if it meant revitalizing the economy in their part of town. It shouldn’t have had to come to this. The city failed trees, and it failed South Dallas.

You might think Caraway and Atkins are wrong. But they’re wrong for the right reasons.

If I didn’t know what Karen Woodard did for a living, if I just walked up to her table at the Cafe Brazil on Davis Street on a dreary, drizzly March morning and started talking to her, I might guess she is a schoolteacher. She speaks in a gentle tone and frequently ends her sentences with an encouraging “right?” Like she’s pulling a roomful of kids along with her toward the right answer.

A Bois d'Arc tree. Photo by Dave Shafer.

But I don’t have to guess. Even if I hadn’t invited her to meet me for a cup of coffee and talk about trees, I’d know that Woodard is a forester for the city of Dallas. It says so in blue script on her white cardigan, right below her name. What her sweater doesn’t say is that she is not just a forester for the city of Dallas. She is the forester.

“I’m the only one,” Woodard says, laughing, not long after I sit down.

She wasn’t the city’s first urban forester. That was Walter Passmore, who was hired in August 2006, after the Dallas Urban Forestry Advisory Committee lobbied for the position and the Texas Forest Service pitched in with a four-year, $100,000 grant. But Passmore left for Austin after a year, and, in September 2008, Woodard was hired as his replacement. She was hired with the intention that she would head up an entire forestry division. Almost seven years later, it’s still just her.

Woodard works for the Park Department, which, with its 381 parks, would be a big enough job on its own. But she also is available to the other city departments and every council district. She looks at master plans and works with developers to fulfill their obligations under Article X. She leads tree planting efforts and attends community events. If it has anything to do with trees in the city, Woodard is likely involved. And she knows what she is up against. The city is just hanging on, barely, to what it has, instead of getting ahead of the curve.

“It’s not a program,” Woodard says. “There’s not an inventory of trees. There’s been people here and there who say, ‘This is what we need.’ And I say, ‘No, you don’t do an inventory, because with an inventory you should have a management plan, right? What are you gonna do if you don’t have the resources to enact that management plan?’ They don’t understand the difference—because we’re just maintaining as best we can, we’re not managing—between those two words. You’d need a structured program.”

When Woodard came aboard, the city did have a structured program, or it almost did. Dallas had recently adopted a management plan for the Great Trinity Forest formulated by Stephen F. Austin University’s Department of Forestry Sciences. “Well, the economy tanked, like January,” she says. “Through that kind of stall-out and now rebuilding, it’s just—” She trails off. But she doesn’t have to finish her thought: there is no management plan.

Which is why, she explains, the process that built the Great Trinity Forest is slowly ruining it. Benign neglect brought a hardwood forest of red oaks, bur oaks, chinquapin oaks, and American elms, as seeds drifted down the creeks and river, and civilization, for the most part, stayed out of the way. But civilization has crept closer, and those trees are being choked out by what’s coming from upriver now: invasive species such as Chinese privet, nandinas, Chinese tallow. The latter turn a beautiful yellow and red in the fall, but they grow so fast that they shade everything else. Those young oaks and elms never get enough sunlight to stand a chance.

If the city had a forestry division, it could handle this—cutting back the invasive species, opening plots of green space so the forest can take care of itself, reseeding, fighting, living, dying, starting over again. Fort Worth could handle this. It has 21 people working for city forester Melinda Adams. They devote resources to it. They are managing, not just maintaining.

“My goal is to—gosh, you hate to say it—be like Fort Worth in that sense,” says Michael Hellmann, the assistant parks director who hired Woodard.

It could be worse. After a few years on the job, Woodard was able to get designated crews she could train and call on for each park district. It’s still a big job—there are more than 60 parks for each district—but it helps. She also has a volunteer group of citizen foresters that helps lead tree plantings (what she calls “woo-woos,” because they get all the attention as far as trees go) and pruning. Because of liability issues, volunteers can’t climb ladders, but “as long as both feet are on the ground, they can prune,” she says. They do a lot of work at Main Street Garden, using pole saws to take the weight off the end, just like Woodard showed them.

“Right now, I’m at 87 citizen foresters,” she says. “Now, not all of them are active. I never made it strict. My thought is, we have classes every fall. If they go through the classes and they never volunteer, I at least have one more person out there that knows this much more, that talks to their neighbors and family about proper pruning and proper planting. Right?”

She smiles. She does that a lot when she’s talking about trees, and her love for them is infectious. And maybe that’s where it starts changing. Dallas may not have a forestry division, or a management plan for the Great Trinity Forest, or a strong enough preservation ordinance. It may still lose trees that it shouldn’t. But maybe Woodard is the oak tree the city needs, seeding the city with knowledge and love one citizen forester at a time.

“I wish I could do more with them,” she says. “I wish I could do more, period. It’s only me.” She laughs. “I have no life as it is. I’m pretty much 24-7.”

Emerald City

To determine where Dallas’ tree canopy was the most at risk, Texas Trees Foundation—in collaboration with Azavea, a spatial analysis firm—studied where development was most likely to happen. They located vacant, privately held parcels of land, then compared those with various city-led initiatives (such as Mayor Rawlings’ Grow South plan), transportation corridors, TIF boundaries, and anything else that might impact standing trees. Once they identified the number of trees in danger, they were able to calculate how much it would cost each council district, in terms of lost benefits. (Note: because the study began before the districts were redrawn in 2013, the map reflects the old boundaries.)

Map illustrated by Peter and Maria Hoey.

Map illustrated by Peter and Maria Hoey.

District 1: $5.5 million

District 2: $9 million

District 3: $64.6 million

District 4: $17.1 million

District 5: $23.9 million

District 6: $18.1 million

District 7: $19.9 million

District 8: $72.1 million

District 9: $10.1 million

District 10: $10 million

District 11: $8.8 million

District 12: $6.8 million

District 13: $9.6 million

District 14: $5.6 million