Oak Wilt: Facts and Fears, Part 2

A tree stricken with Oak Wilt. All photos by Steve Houser.

Published January 25, 2011 By STEVE HOUSER

Last month’s article covered basic information about Oak Wilt and its symptoms, along with an introduction to its transmission. The article noted that there is much confusion and misinformation regarding Oak Wilt, and research goes only so far in providing the answers to important questions. Future research will likely change current recommendations — which is a good thing. Early detection and an accurate diagnosis, paired with a solid management plan, are critical to managing the disease successfully. In some cases, there may be a need to develop a management plan for an entire city block or particular part of a community.

Management/Diagnosis

Symptomatic Live Oak leaves.

An Oak Wilt diagnosis can be confirmed in a laboratory by isolating the fungus from diseased tissues. Taking tissue samples is not a simple process and should be left to someone with specific training and experience. Each step of the process must be done properly. Although all the symptoms indicate Oak Wilt is present, lab reports may return as a “negative.” A negative from the lab does not mean the sampled tree is not infected, only that the fungus could not be found in the particular sample provided. Note that “someone with specific training and experience” is typically a consulting arborist, but may also be a forester or Oak Wilt researcher.

Management/Suppression

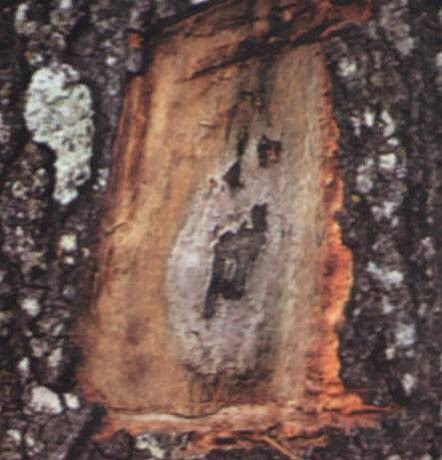

Fungal spore mat.

As previously noted, fungal spore mats form only on species in the Red Oak group and produce a fruity odor that attracts the Nitidulid beetle — believed to be responsible for the overland spread of the disease. As a result, infected and dying Red Oaks are a greater concern, due to the potential for aiding in the overland spread. There is no evidence that Live Oaks contribute to the overland spread. The firewood and stumps from removed Live Oak trees are not a concern.

Since the spore mats have been known to form on stumps and firewood of species in the Red Oak group, infected trees should be promptly removed from the site and chipped, burned or buried. If this is not practical, remove the infected tree’s bark from

Avoid storing infected Red Oak firewood near healthy trees unless it is “seasoned” or completely dried for at least one year. If infected Red Oak wood must be left on a site, it should be covered with clear plastic and the edges buried in the soil. Avoid purchasing Red Oak firewood that appears green and not ready to burn. However, burning infected Oak firewood of any species will not spread the disease since the heat of the fire will destroy fungal spores.

The disease is most often spread by root-to-root contact. In a dense group of Live Oaks, Oak Wilt can expand outward to 75 feet or more each year. Trenching between infected and non-infected trees is a method of suppression in a rural setting, but it is difficult and less successful in an urban area due to the number of underground utilities and obstructions.

By comparison, Oak Wilt centers in the Dallas/Fort Worth area do not appear to be expanding outward as rapidly as centers found in Austin. One theory is that the disease expands more rapidly in communities with indigenous populations of Red Oak and Live Oak. These populations have root systems that are more interconnected than an urban forest established primarily by planting new trees. One of the primary indigenous Oaks in North Central Texas is Post Oak (Quercus stellata), which is extremely tolerant of the disease. The same is true for Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) and Bur Pak (Quercus macrocarpa), which should be planted more often for this reason. Are you starting to lose some of your fears yet?

Next month`s article will cover Oak Wilt Management/Pruning. The final article will address Prevention and Treatment. Afterward, we hope to have fewer nervous tree mothers!!

To continue learning about Oak Wilt, click here for Part Three of this article.