Tree Planting: Selecting a Tree, Part Two

Published October 30, 2014 By STEVE HOUSER

Once you have determined a planting location, selected a tree species, and resolved any potential conflict with underground/overhead utilities, consider the optimum size of tree to plant for your circumstances. This decision is typically based on what your budget will allow and how quickly you want to begin enjoying the benefits of having a tree.

Trees can be planted any time of the year, but fall offers the best planting results because the root system will grow vigorously and begin establishing new roots before the next hot summer. If you transport a tree during the growing season (spring and summer), always cover the foliage with a tarp or shade cloth, or the tree can be completely desiccated (dried out) before reaching its destination. Trees don’t mind a warm gentle breeze, but traveling “mach four with your hair on fire” is cool only if you are a Top Gun.

You might find it interesting to know that if you plant an acorn, a sapling, and a balled-and-burlapped tree ranging from one inch in diameter to ten inches in diameter, all in a row, 20 years later it is likely that you will have trees all about the same size. The term “balled-and-burlapped” refers to trees that are field grown and dug for transplanting by placing burlap around the root ball. While digging balled-and-burlapped trees is a standard nursery practice, it can result in a loss of up to 50% or more of the tree’s root system. Therefore, a three inch diameter tree can take two years to redevelop roots and start to grow, whereas a ten inch caliper tree could take up to five years before it is fully established and begins to expand its canopy. The ten inch caliper tree can cost thousands and provide an immediate effect, whereas a two inch tree costs relatively little and requires patience for a few years. As a result, a two to four inch tree is the optimum size or most property owners to either plant themselves or have planted by a landscape contractor.

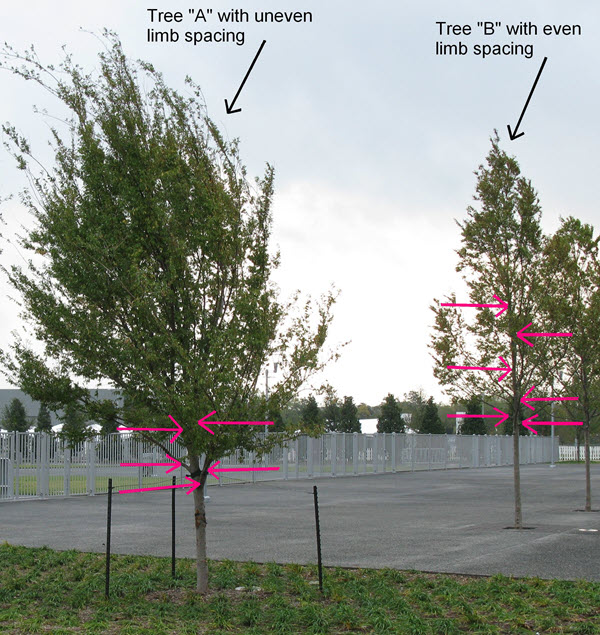

Tree “B” has branches evenly spaced along the main trunk, which will result in a structurally superior tree as it matures. Tree “A” has branches that will interfere with each other as the tree grows.

If the budget is tight or you are a do-it-yourselfer, plant an acorn, bare root tree, or containerized sapling by following the recommendations in this previous article. Be sure to keep the roots of these trees moist at all times, as they can dry out quickly in the open air.

If you can identify the smaller valuable trees (Oaks, Pecans, etc.) that the animals often plant in your flower or mulch beds, you can transplant them to a pot or a spot in the yard.

Containerized trees enjoy the benefit of rooting-in quickly, but they may have problems with circling roots. A balled-and-burlapped tree will have a much better root system, especially if it has previously been root pruned.

Multi-trunk trees may have root systems that are compromised by competing roots and may not be able to support or anchor the trunk they serve.

Whether you plant your new tree yourself or hire a company, here are some things to look for:

- Visit a reputable nursery or contact a reputable landscape contractor with experienced and knowledgeable staff.

- Avoid purchasing trees with more than one trunk. Their root systems are often poorly distributed beneath the trunks, and it may be difficult to keep them from tipping over.

- Look for even branch distribution along the main trunk rather than several limbs growing closely together off the main trunk. The former will be more structurally sound as the tree matures.

- Avoid trees with major limbs that cross or with limbs that form tight “V” shapes. Those “V” branches are weak and can easily split in wind and ice storms. Choose trees with deep “U” shapes or 45 to 90 degree angles, which are stronger.

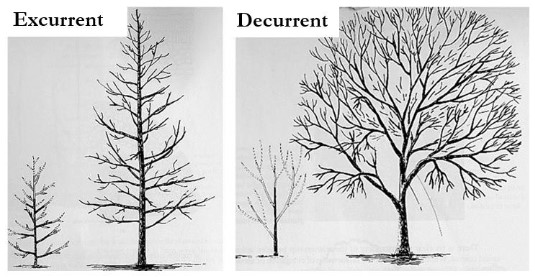

- Avoid trees with co-dominant stems or two or more limbs that compete with each other for dominance. An “excurrent” growth form is stronger than a “decurrent” form.

- Check the trunk and primary limbs for wounds, scrapes or sap oozing out of the trunk. Oozing sap can be due to a wood-boring insect.

- Check the twigs to be sure the buds are healthy; scratch a twig with your thumbnail to be sure it is green, healthy and full of moisture.

- Check the smaller roots to be sure they are white and healthy rather than brown or dry.

- The tree should not have the ends of the limbs or top cut back to a stump or stumps.

- Check the root ball size of a balled-and-burlapped tree. It should be at least ten to twelve inches for each inch in trunk diameter for most tree species. (Trees up to four inches in diameter are measured at six inches above the ground and trees between four and twelve inches are measured at twelve inches above the ground.)

- Check to be sure no roots are circling or binding the base of the trunk. These can cause problems down the road as both the trunk and root expand, putting pressure on each other. (Similar to being joined at the hip with an unsavory relative … not ideal.)

A healthy urban forest equals a healthy community.

Trees with a “decurrent” form have broad canopies with branching habits that may be weak and subject to breaking. Trees with an “excurrent” form have a single leader trunk and branches with strong attachments.

To continue learning about tree planting, click here for part three of this tree planting article series.