Searching for a Sign

Published November 28, 2016 By TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

The battle to document and save old trees that may have once marked native American trails.

Six months before the stock market crash that plunged the country into the Great Depression, Richard Gloede, a landscape architect and the owner of a nursery in Evanston, Illinois, wrote a letter to General Abel Davis, the chair of the Cook County Forest Preserve’s advisory committee. He implored Davis for help in protecting the “old Indian trail trees” along the shores of Lake Michigan. “I have located on the North Shore alone over one hundred and have photographed, measured them according to size, condition, which way they point by compass, etc.,” Gloede wrote in a letter dated March 22, 1929. “It seems to me that these trees should be put in the best of care and kept so.”

The trees in question, often referred to as trail marker trees, would not have been hard to find. Each made two roughly 90-degree bends so that a portion of the trunk grew horizontally, parallel to the ground, forming a shape that can best be described as one half of a field goal post. Today, thousands of trees with this distinctive double bend have been documented in the United States, and there is evidence that at least some of them were manipulated on purpose, shaped by indigenous peoples to provide landmarks where others did not exist.

Like us, North America’s early civilizations needed navigational tools, and in heavily wooded areas like the Southeast or the Great Lakes regions, natural landmarks like mountain peaks were few and far between, and rock cairns, unlike in Utah and Nevada, would have been difficult to make and impossible to see from a great distance. That left trees. A shaped tree could serve as an early road sign, a way to navigate the landscape.

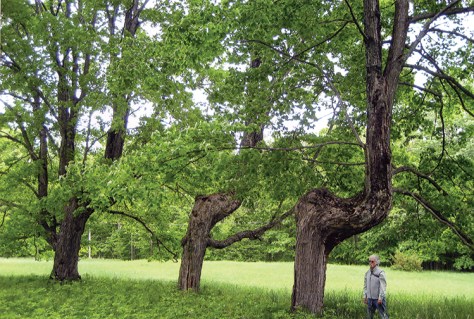

Dennis Downes at a council circle near Charlevoix, Michigan. Unlike some living council circles, these maples appear to have been shaped. Image courtesy of Dennis Downes.

In Gloede’s day, this was, if not common knowledge, mostly undisputed. Trail marker trees appeared in newspapers and scholarly journals and were seen by many ordinary citizens as living landmarks, “reminders of old Indian days,” according to a 1920 article in the Chicago Daily News, which included a photograph of a young woman sitting sidesaddle on the horizontal trunk of a bent tree, reading a magazine. Gloede and other landscape architects believed that Illinois’s trail marker trees had educational value and should be used to teach children about the indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region. But little ever came of his letter. In 1940, after Gloede’s death, Robert Kingery, a member of the forest preserve’s advisory council, wrote to Davis’s successor, inquiring as to whether or not the matter should be reopened and these trees “properly charted and…given special care.”

There is no indication that the Cook County Forest Preserve ever acquired Gloede’s photographs or mapped the locations of any of the trail marker trees. Time passed. Many of the individuals with knowledge of these trees died or moved away. Most of the trees in Illinois slowly disappeared, but interest in them never fully died out.

In a 1941 article for the Scientific Monthly, for instance, the geologist Raymond Janssen wrote about trail marker trees, asserting that “trees were sometimes bent by the Indians to mark trails through the forest” because they “were the most accessible and most easily adaptable materials at hand.” They could be manipulated to varying levels of conspicuousness and therefore “made ideal guide-posts,” he wrote. The topic was newsworthy enough—and the evidence credible—that Time magazine ran an article inspired by Janssen’s research later that same year.

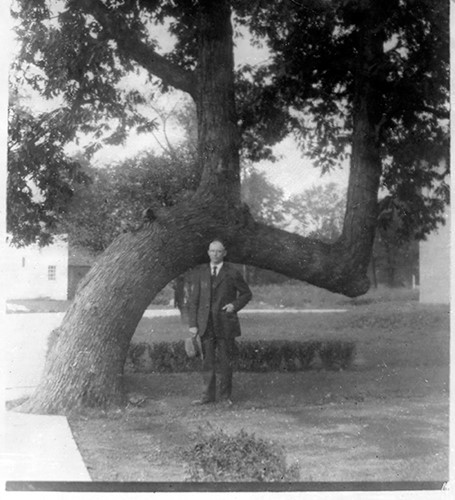

Half a century later, these trees are no longer fixtures of our cultural imagination. They do not appear in our journals or adorn our maps. The last known trail marker tree in Winnetka, Illinois, a double-trunked white oak known as the Fuller Lane Tree, died and was removed in 1984, along with a bronze plaque stating that “this ancient white oak, one of many originally found on the North Shore, was presumably bent by the Indians about 1700, marking a trail to Lake Michigan.”

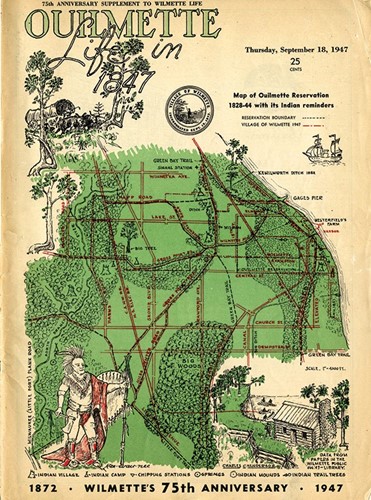

A 1947 map depicting life in Wilmette, Illinois, in 1847 includes the location of trail marker trees. Image courtesy of the Wilmette Historical Museum.

The trees that have survived are reaching the end of their natural life span, and many are worried that, without sufficient education, these important and underappreciated artifacts of early North American culture will soon be gone, taking with them a clue into how indigenous peoples navigated their world.

Dennis Downes has picked up where Gloede and Janssen left off. In 2013, more than 80 years after his initial letter, Gloede’s family auctioned off hundreds of the landscape architect’s photographs. They were bought by Downes, a painter and sculptor who grew up on the North Shore, a string of affluent suburbs that includes Evanston, Winnetka, and Highland Park. Over the past 30 years, Downes, who, with a white handlebar mustache and white shirt under a black leather vest, looks plucked from the pages of a history book, has driven hundreds of thousands miles across the United States and Canada to find and photograph these bent trees, visiting some states more than two dozen times and amassing a trove of photos and documents that suggest that some indigenous tribes did, in fact, bend trees for use as trail markers. In the early 1990s, Downes formed the Great Lakes Trail Marker Tree Society and eventually published a book, Native American Trail Marker Trees: Marking Paths Through the Wilderness.

Of course, nature can also bend trees—into Ls and Zs and every shape in between—and this has led to skepticism. Some argue that these trees are not part of some vast navigational network but the result of natural causes, bent by animals, windstorms, or other trees, which could have fallen and pinned the bent tree to the ground as a young sapling. Don Wells, a retired civil engineer and one of the founders of a group called Mountain Stewards, which has built a database of more than 2,000 trail marker trees, has encountered significant resistance, particularly within the academic community. “They say, ‘Look, none of our fellow PhDs wrote anything about this. Therefore it doesn’t exist,’” he says.

Downes and others have continued to gather evidence, searching for any reference to these trees in old newspapers and journal articles. It was shortly after his book was published that Downes acquired Gloede’s photographs. Among the hundreds of old glass slides was something he had only ever dreamt of seeing. It was a fuzzy, black-and-white image that seemed to show a tribal leader standing atop a bent tree, smudging stick in hand, mid-blessing.

“When I held that up to the light, I was extremely happy,” Downes says. The man in the photo, he says, was Chief Evergreen Tree, a tribal leader associated with the Ho-Chunks in Wisconsin. The photograph had been taken at a commemoration hosted in 1928 by the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution and attended by all manner of dignitaries, including Anne Ickes, the wife of Harold L. Ickes, who later became the Secretary of the Interior. Downes had written about the event in his book, “but I had no physical evidence” of the chief’s presence, he says. “Now, I have the chief standing on the tree, giving the tree its name, ‘Leading Boy.’”

It’s tempting to see trees as ephemeral, and therefore lousy, landmarks. For one, they’re living things. They have a life span—a beginning and, inevitably, an end. They’re susceptible to storms, wildfires, disease, pests. But before large-scale industry came to North America, before logging and modern development and the introduction of invasive species, hardwoods like oaks and beeches would have seemed practically invincible to indigenous peoples, outliving multiple generations and representing strength and longevity.

We actually still use trees to mark the landscape. In northwest Arkansas, not far from one of the hundreds of trail marker trees that have been documented in the area, is a white oak with a canary yellow sign nailed to its trunk. “Bearing Tree,” the sign reads in big, blocky type, followed by a series of numbers scratched into the metal in a childlike scrawl. Bearing trees, or witness trees, as they’re sometimes called, are used by surveyors to provide the bearing and distance from what’s known as a corner monument, which marks a property corner. If a corner monument has been disturbed or moved, the bearing tree can be used to identify the property boundary. Like road signs—but unlike trail marker trees—they are legally protected. Tampering with a bearing tree is a federal offense.

Our use of bearing trees is an echo of indigenous peoples’ understanding of trees as worthy wayfinding devices, monuments that often outlive man-made markers. But it also was the beginning of the end for indigenous peoples, whose way of life would be forever affected by the acquisition, division, and subsequent sale of lands they once inhabited. The Public Land Survey System, originated by Thomas Jefferson and officially created by the Land Ordinance of 1785, overlaid onto the landscape a grid of 36-square-mile townships and square-mile sections, laying the groundwork for the system of private land ownership we have today.

We can’t do much about actions taken 250 years ago, but Andrew Johnson, a member of the Cherokee Nation and the executive director of Chicago’s American Indian Center from 2013 to 2015, says that renewed interest in trail marker trees has played a significant part in the reclamation of his people’s history and helping to assert a counternarrative. The fact that trail marker trees have been identified throughout the United States, and not just in a particular region, means that tree shaping was a practice of multiple tribes, he says, providing additional evidence for a sophistication and scale in navigation that he believes was denied early North American societies.

The trees also bolster recent studies that put indigenous populations well above earlier estimates, a subject explored in Charles Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. “As science advances, it’s catching up to what the true numbers are,” Johnson says. “The depth of trade and travel, to sustain that on a macro level, is quite remarkable.”

Gloede wasn’t the only landscape architect to recognize the existence of trail marker trees. Jens Jensen, who lived and worked in Highland Park on the North Shore, was fascinated by these living road signs. He wrote about the importance of indigenous marker trees in journals such as American Forestry and spoke at a variety of events, including the dedication of a bronze plaque that was placed near a trail marker tree in Glencoe in 1911.

It’s well documented that Jensen was heavily influenced by tribal practices, specifically the use of council circles, an element that appears in dozens of Jensen’s own projects. “He certainly had a fascination with Native Americans and their history in the landscape, and I think he also was struck by stories of places in the Midwest where there were these council groves,” says Robert Grese, ASLA, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Michigan and the author of Jens Jensen: Maker of Natural Parks and Gardens. “He felt there was a rich history [there]—that these trees had dated from pre-European settlement periods.”

Grese says there’s also evidence that Jensen wove old Indian trails into landscape projects for clients such as Henry Ford. At Fair Lane, Ford’s estate outside Dearborn, Michigan, Jensen believed the existing road followed a former footpath. “He was very insistent on keeping that as part of the overall landscape,” Grese says. “That was pretty common.” He says Jensen was known to scour historic maps so that he could incorporate indigenous trails as garden paths.

Downes believes Jensen likely knew of the living council circles that once existed throughout the Great Lakes. He shows me photographs of a council circle that still stands, outside a tiny town called Charlevoix near Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The maple trees, which are evenly spaced and form a nearly perfect circle, look to be hundreds of years old. Their canopies have intertwined, forming a leafy green parapet around a large swath of grass. There’s something else distinct about these trees, something you can’t see in any of the aerial photos: All their trunks are bent.

To determine whether a tree is a historic marker or simply an accident of nature is a complex and messy process. Even now, there is little agreement as to what criteria should be used. The most basic requirement, one that everyone agrees on, is age. “It has to be old enough,” says Steve Houser, an arborist in Dallas and a cofounder of the Texas Historic Tree Coalition, which helps document and preserve potential marker trees as well as other notable specimens. “I have people send me 10-inch trees, and it’s like, no, they have to be at least 144 years old. It’s been 144 years since the last free-roaming Comanche was in the state of Texas.”

The second is shape. Most have the double bend, which, according to several theories, was created by bending a sapling down toward the ground, often pointing toward or parallel to whatever was being marked, and tying the tree with rawhide or cord. Over time, the top of the tree, no longer able to get enough sunlight, would begin to die, and the tree would send up new vertical limbs. The top would rot or be cut off, as would any unwanted sucker branches, leaving the tree with a shape that, once the tree was old enough, could not be altered. In northern regions, the bend often appears higher up the trunk, possibly to ensure visibility even after heavy snows. Houser says trail marker trees show signs of being contorted at an early age, and he looks for other signs, too: “thong marks or scars” from where a tree was tied down.

A bearing tree in northwest Arkansas, a modern use of trees as markers. Photo by Timothy A. Schuler.

But the real key, Houser says—and this is the messy part—is to establish a linkage between the tree and either a known cultural site or a topographic feature that would have been useful to indigenous peoples: a stream crossing, for instance, or a natural shelter that might have been used as a campsite. “I have to find that connection between the Comanches, in my case, and a site at a particular time near the age of the tree,” Houser says, a process he describes as reading the landscape. “I look at early trail maps and their association to the tree: Is it pointing the way of an early trail? We look at topo maps: What was the topography like back then? What would they likely have been pointing toward?”

Indigenous peoples probably used naturally deformed trees as wayfinding devices, too, Houser says, so just because a tree is bent, and is located near a known cultural site, doesn’t mean it was shaped. Conversely, just because a tree wasn’t shaped doesn’t mean it wasn’t used as a marker. Which makes it all the more difficult to decide whether or not a tree should be considered historically or culturally significant.

Opinions also vary on who can make the ultimate designation. Houser believes that only tribal members should be allowed to make the call, and the Texas Historic Tree Coalition won’t recognize a trail marker tree unless it’s verified by the Comanche. But he admits that he’s lucky, living in Texas. “The Comanches are much more open about it,” he says. In other parts of the country, he says, “if the elders still exist with the tribe, the next question is, do they share that information? A lot of them don’t want to, and for good reason.”

Centuries of exploitation have made many tribal elders reluctant to share what they know with outsiders, says Don Wells, of Mountain Stewards, whose group has released a book and a documentary film about trail marker trees. “For a long time, they didn’t want to talk to anybody about [these trees] because people were going and destroying them,” he says. Sometimes the acts were racially motivated, other times by the belief that the trees pointed to buried treasure.

Indigenous knowledge also is fading out. Some nations have no record of shaping trees. Johnson says this could mean that those tribes never did it, or it could just mean that, at some point, the practice was not passed on. “Natives have an oral tradition,” he says. “If you break that tradition by one, two, three generations, then it’s impossible to get [the knowledge] back.”

In areas where tribes can’t or won’t acknowledge these trees, how can a tree’s authenticity be verified? Some have tried scientific methods. A few years ago, Wells collaborated with dendrochronologists from the University of West Georgia to core and date several potential trail marker trees, in order to confirm that they fall within the proper age range. But some felt that this desecrated the tree, and he was asked to stop. Johnson sees little need for conclusive evidence, which he says is a product of Western thinking. “From a native standpoint, we don’t feel that we need a scientific verification,” he says.

The landscape architect Richard Gloede in front of the Fuller Lane Tree in Winnetka, Illinois. Image courtesy of the Winnetka Historical Society.

These two perspectives are slowly aligning. The National Park Service has begun to acknowledge the existence of what it calls “culturally modified trees,” which includes bent trees but also burial trees and arborglyphs, a number of which have been identified at the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument in Colorado. However, it’s thought that these bent trees may have been ceremonial in nature, rather than navigational. More recently, Houser coauthored Comanche Marker Trees of Texas with the anthropologist Linda Pelon and the Comanche historic preservation officer Jimmy Arterberry. Houser’s book, which was released in September, is the first on trail marker trees to be published by a university press.

Houser says his goal with the book was to preserve, at least on paper, these marker trees, which may be one of the last remaining windows into a culture that has never fully been appreciated. “We can’t preserve what we haven’t taken the time to find and recognize,” he says, adding that it’s now or never for these rapidly decaying landmarks. “We can’t wait 20 years to catch up on this work. We’re losing ’em as fast as we can look at ’em sometimes.”